“If you reject the food, ignore the customs, fear the religion, and avoid the people, you might better stay home.” – James Michener

Reality is Harsh

There are at least two sides to the Caribbean tourism industry: the side travelers experience as they transit from airports in air-conditioned vans and limos to their hotels, and the locals’ side – the neighborhoods where tourism employees live, go to school, visit with friends and family and hold parties and enjoy playtime.

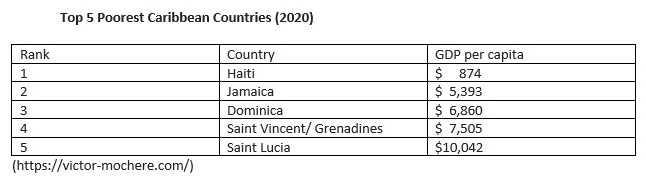

While tourists are spending over US$1300 per night (excluding taxes and fees) at Sandy Lane for hotel accommodations in Barbados, the people providing the luxury experience are unlikely to be able to afford even one evening at the property. The average gross salary for a hotel manager is BBS 60,000 (US$30,000); housekeeper: BBD26,000 (US$13,000); receptionist: BBD 21,012 (US$10,506) (averagesalarysurvey.com, 2019). A bartender in Barbados earns between BBD 670 per month (US$331.90) to BBD 2,070 per month (US$1,025.43) (2020).

In Trinidad and Tobago, travel and tourism managers’ average gross salary – TTS 105,000 (US $16,078); hotel manager, TTS 406,200 (US$60,431); tour guide TTS 80,000 (US$11,941); housekeeper, TTD 30,000 (US$4,691). At the Villas at Stone Haven in Trinidad/Tobago, a one-night stay at a one-bedroom cottage will cost US$766.00 – including taxes and fees (google.com/travel/hotels/Tobago).

Times BC, Before COVID-19

Before COVID-19 took over the world, the Caribbean region was experiencing a tourism boom. Air arrivals to the wider Caribbean region were up by 12 percent in the first quarter of 2019, the region’s highest growth rate at that point on the calendar in years. This includes:

• I9.1 million international tourist arrivals to the region in the first three months of 2019, representing an increase of almost 970,000 visitors to the Caribbean.

• The region’s cruise industry also saw growth, with a jump of 9.9 percent in cruise passenger arrivals and a record total of 10.7 million arrivals in the period.

• The United States remained the region’s largest tourism source markets, accounting for 4.5 million tourists in the period, while Canada sent 1.5 million visitors to the Caribbean, representing a 4 percent increase.

The Caribbean island nations rely heavily on tourism for employment and it provides more than 90 percent of all jobs in Antigua and Barbuda. In 2019, one in every 10 people in the Caribbean worked in travel and tourism-related occupations, contributing $8.9 trillion (approximately 10.3 percent) to the global economy.

With the arrival of COVID-19, the industry is hemorrhaging jobs and revenue, with the worst yet to arrive. The largest loss of tourism arrivals due to the pandemic include) the Bahamas (-72.7 percent), Dominica (-69.1 percent), Aruba (-68.1 percent), St. Lucia (-68.5 percent) and Bermuda (-61.7 percent).

Cock-eyed Optimist or Magical Thinking

Even with the world told to quarantine, not to travel, and not to mix and mingle with others at bars and restaurants, marketing efforts for the Caribbean region continue to direct their efforts to motivating tourists to get on a plane or ship and head to the Caribbean. The public relations and advertising efforts remain ever faithful to portraying a fantasy land that offers no alternatives to eco-tourism and keeps the dark sides of the Island nations out of the mindset of the visitor.

Many island destinations have state-of-the-art airports with Pina Colada’s welcoming each and every arrival. Ground transportation at the terminals quickly transport arrivals to their hotels with drivers trained in the art of “chit chat.” The drivers talk, (sometimes incessantly) with the intent of keeping passengers distracted from the poverty that surrounds the ports. The animated (and frequently interesting) information from the drivers may include updated weather information, the temperature of the sea, and local history. In many cases, the drivers encourage visitors to talk about their hometowns, the length of time it took them to arrive and what they plan to do during their holiday.

By the time the conversation has dwindled down to children and pets, visitors are at their hotels, entering the reception areas, registered and delivered to their rooms and suites by attractive employees with sincere smiles and warm greetings. Between breakfast and dinner, guests are entertained by island music, local drinks and international gourmet dining options that, in many instances, keep them within the walls of the hotel for their entire holiday.

What lies beyond the palm trees is outside the interests, wants and needs of the international visitor. The fact that employees are paid minimum wages, that increasing levels of crime have eroded confidence among investors and reduced international competitiveness by introducing much higher costs in the form of additional security or transactional costs is of no interest to these tourists. The fact that crime is causing capital flight, along with the loss of people with skills or education, who are choosing to work in safer more secure locales is of no consequence to these guests and the hoteliers do their best to make sure that none of the harsh reality of the destination enters this dream-like vacation experience.

Another Slice of Life

Visitors willing to step outside the gated holiday communities, and dialogue with local residents, are likely to find that crime diverts limited resources away from health and education to security. In many islands research suggests that citizens are currently more concerned with crime than they are with other issues such as unemployment, healthcare and family abuse.

In 2019, the highest homicide rate was registered in Venezuela, with over 60 murders committed per 100,000 inhabitants (statista.com). Jamaica (2018) recorded a homicide rate of 47 homicide per 100,000 inhabitants with an uptick of 3.4 percent one year later (2019) (osac.gov) which is three times higher than the average for Latin America and the Caribbean. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) cited crime as the number one impediment to economic growth and the government of Jamaica found that corruption and the transnational crime it facilitates presents a grave threat to national security (osac.gov/). Forbes Magazine listed Jamaica as the third most dangerous place for women travelers (2017) and Business Insider ranked the destination the 10th amongst the most dangerous places in the world (2018).

The US Department of State Travel Advisory assesses The Bahamas at Level 2, indicating that travelers should exercise increased caution due to crime. Incidents involving US citizens include rape, sexual assault and robbery/theft and armed robbery, property crime, purse snatching, fraud and sexual assault remain the most common crimes perpetrated against tourists (osac.gov).

The Caribbean waterways have seen an increase in US naval presence focusing on countering narcotics trafficking in semi-submersible vessels and shipments of sanctioned fuel and goods from Iran to Venezuela.

Although tourists enjoy Caribbean activities that include sailing, swimming and scuba diving, the sea offers other more nefarious activities. Before the pandemic the cruise industry disgorged thousands of visitors, introducing them to the illusion of prosperity. Most of the islands pay a per head fee to the cruise lines for each passenger who goes ashore. Cruise passengers do not care that the ships destroy the reefs and sea life and have a stranglehold on the discretionary dollars’ passengers spend. In addition, the cruise ships, beloved by millions of global travelers, delivered COVID-19 to many destinations and local citizens at the beginning of 2020 because company executives were impotent when it was time to be pro-active against the virus contagion. To compound the problem, many ships were stuck at sea with COVID-19 patients onboard – so passengers and crews were unable (not permitted) to disembark.

The pristine reefs of Bonaire (Dutch) make this island a popular port of call and cruise lines disgorge up to 4000 passengers at a time. Sometimes the ships have triggered food shortages by taking up dock space usually reserved for cargo. Groups like Bonaire Future Forum: Opportunity from Crises have debated whether the island should limit access to specific ships with more expensive itineraries and hence more selective in passenger profiles.

Rebalance Tourism

If there is to be future for tourism in the Caribbean region, perhaps it will come by taking a pause in tourism growth with the time used to reevaluate the tourism product. Climate change, species extinction, deforestation, child labor, sexploitation and many other “evils,” represent a wholesale failure of mass tourism.

The first steps require an honest appraisal of regional assets and a dedication to sustainability and local entrepreneurship. Mass tourism has been accompanied by significant dependence on foreign investment in development, promotion and property management. The “industrial” size tourist complexes have been unregulated and poorly planned resulting in growth besieged by volatility and vulnerability leading to, in many instances, financial crises.

The combination of bio-physical threats such as volcanic eruptions, and environmental changes leading to intense hurricanes and rises in sea levels combined with economic upheavals from severe global recessions lead to the current COVID-19 health and economic crises. The last few decades have put enormous pressures on the tourism-industrial complex and there has been little time to review and consider lessons learned. Given the fact that tourism has become the most important economic asset of the region, it is unfortunate that previous disasters appear to have been ignored; however, going forward, they may provide the foundation for a sustainable future.

For the region to continue and prosper it must adjust to imminent competition and the changing demands of the global marketplace; therefore, it needs to recognize and prepare for a renewal, revitalization and repositioning of its product. As an industry, it must acknowledge its vulnerability and volatilities and be willing to document and clarify the unique aspects of its assets and practices that differentiate one island from another and one culture from another while protecting the remaining assets from further destruction.

Islands most noted for eco-tourism include Dominica, known as the Nature Island of the Caribbean, where 65 percent of the land is tropical rainforest and more than 300 miles are dedicated to hiking trails. Bonaire is noted for its pristine marine environment while Costa Rica and Belize are renown for being ecologically friendly. Resorts on these islands are low-impact with commitments to reduced energy use or renewable energy with visitor activities encourage learning about and enjoying the local ecosystem.

Running Parallel to Mass Tourism

The new eco-tourism approach will focus on the quality of the tourism experience rather than on the quantity of tourists arriving by air or sea. The quality experience will not be based on the dollars spent by the visitor, but rather the richness of the moments that will be culturally sensitive, focusing on the human side of the destination. The control of the new tourism product will not be in the hands of bankers or foreign investors, but rather regulated and directed by local entrepreneurs and their representatives.

The current focus on mass tourism and on creating a large revenue stream requires a constant increase in the numbers of tourists who are moved through the system with little or no concern for the quality of the tourist experience or the benefits that could accrue to the local service providers. In addition, the profits from mass tourism leak out of the country, ending in foreign banks and shareholder pockets.

WOKE Visitors

The new niche markets will encourage visitors with a “woke” consciousness who are happy in supporting local entrepreneurs and their communities. These new visitors will do their best to minizine their footprint in the destination as their interests and desires are to slow their pace, seeking rest, recuperation, wellness and learning; these travelers prefer to be viewed as GUSETS and not as consumers with credit cards, bank accounts and stock portfolios. Accommodations and attractions will feature remote locations that are handicap accessible and designed for spaces overlooked as prime locations for mass tourism development.

The new entrepreneurial tourism product will emphasize the personal touch currently absent from assembly-line tourism where people, places and attractions are treated as commodities. Eco-tourism will focus on a bionetwork, with an emphasis on conviviality, sense of place and the human touch. New, ecology-based tourism experiences will feature local assets: fishing, scuba diving, snorkeling, bird-watching, marine turtle watching and preservation, and Caribbean style leisure activities including sailing, kayaking, walking, swimming, hiking plus cooking and crafts – taught by local artists and chefs.

New “All-Inclusive”

Culinary menus will re-establish dining options that have been lost as mega- hotels and restaurants moved from local food groups to international cuisine. Locally trained chefs, using food from nearby farms, will encourage a new appreciation for the culture and customs of each island nation. Meals, evening meetings, communal parties, musical and cultural events, all the way through to shopping for arts and crafts from residents – will feature what is available through entrepreneurs and shared with friends and family – creating a new definition of “all inclusive.” Old businesses will be revived – from raising chickens and cattle, to agriculture and agri-processing plants.

Marketing

Ecotourism marketing will focus on experiences that are nature based. Some studies have found that many tourists (83 percent) like the idea of being green and protecting the environment. Green washing- the “lets-pretend” concept of ecotourism is not what ecotourism is about. One of the concepts of Green Washing is a deceptive form of marketing as the vendors and their consultants promote places that are NOT protected by environmental norms or regulations or eco-trips that have environment friendliness in name only. Tourists visit a destination, return home, believing they have helped the environment and they have not. Such programs and procedures must be identified and removed or changed – it is no longer acceptable to dupe the unsuspecting tourist.

The new ecotourism opportunities can be marketed globally at a budget-level because of new technology that makes e-marketing available to entrepreneurs with small bank-accounts but large skill-sets and a clear vision. Businesses will be promoted through entrepreneurial designed websites, offering personalized holiday itineraries and experiences – not tours designed by global tour operators. Individualized experiences will be directed by local historians and community leaders who are able to provide this unique niche for alternative holiday opportunities.

Government

Oversight and political support from government agencies will ensure that the stakeholder’s entrepreneurial rights are honored and will prevent foreign or outsider takeovers. Centrally supported, public/private partnerships will enable a competitive environment of quality offerings that are sustainable alternatives to mass tourism.

Government leaders will:

• Direct revenues to the conservation and management of natural and protected areas

• Recognize the need for regional tourism zoning and visitor management plans that are slated to be eco-destinations

• Prioritize the use of environmental and social baselines studies and monitor long-term programs in order to assess and minimize impact

• Ensure that tourism development does not exceed the social and environmental limits of acceptable change as determined by researchers in cooperation with local residents

• Build infrastructure that is designed in harmony with the environment, minimizing the use of fossil fuels, conserve local plants and wildlife and blend with the natural environment

Fit for the Future

While the Caribbean has its flaws, it has an abundance of natural assets that are of importance to the planet. With the right stewardship (public and private), the island nations can become the prototype for what ecotourism can and should be as we transform the idea of tourism from a production line, mass-marketed corporate business model to a new ecology-based entrepreneurial initiative that will flourish in the 21st century.

© Dr. Elinor Garely. This copyright article, including photos, may not be reproduced without written permission from the author.