Tourism is an economic engine for many countries, and it has grown exponentially since the 1970s when less than 200 million people traveled outside their own country for a holiday; in 2019, over 1.5 billion travelers were considered tourists.

For both leisure and business travelers, the infrastructure for travel experiences is “expected.” From public and private transit to/from airports, to marine ports and train stations all the way to their destination and seamlessly securing reservations for hotels and restaurants – all parts of the tourism equation are taken for granted.

Over 44 countries rely on travel and tourism for more than 15 percent of their total share of employment, and COVID-19 has devastated their economic base, with distinct hardships falling on island nations. In Antigua and Barbuda, with a total population 97,900, 91 percent of the population is employed in travel and tourism. Aruba, with a population of 106,800, 84 percent are employed in travel and tourism. St. Lucia, with a population of 183,600, 78 percent are employed in the travel and tourism industry, and the US Virgin Islands, with a population of 104,400, 69 percent of its citizens work in travel and tourism related industries (visualcapitalist.com, 2019).

Not Everyone Agrees

Governments consider the hotel, travel and tourism business sectors to be a beneficial to the economy. Business and political leaders, desperate for foreign currency, are eager to fill hotel rooms, restaurants, bars and beaches and willingly throw caution to the wind, disregarding health professional recommendations for stopping (or corralling) COVID-19.

Unfortunately for the industry, restraint is necessary when approaching the pandemic as the overcrowding of people from around the world in confined spaces plays a major role in spreading COVID-19. From airlines carrying infected passengers and employees from one part of the world to another, and cruise ship passengers and crew spreading the virus from few to many people, tourism has become a pariah among major business sectors for unwittingly contributing to a global recession and unwilling (or unable) to mitigate the catastrophe.

Many businesses, and government executives as well as politicians in the Caribbean and other beach–focused destinations are keen to have tourists return; however, not everyone with a stake in the locale is of the same opinion. The money being spent to fund extensive marketing campaigns to encourage visitors to come back is countered by the fear of potential virus transmission from tourists to local citizens.

This is not the first time that the tourism industry has been disrupted by global events; however, because of the nature of this pandemic and its global scale, the impact is likely to last longer and dig deeper into the hotel, travel and tourism industries with associated (and dependent) vendors and suppliers being destroyed in their wake. Chain hotels located in beach destinations are likely to survive as they are in a position to halt activities (or scale back) while offering support to furloughed employees; however, smaller, entrepreneurial business owners are unlikely to be in similar financial situations and are vulnerable to failure because of the sudden loss of income.

Go to the Beach

Many visitors select a beach as a holiday destination because they want to relax, escape and engage in water-related recreation. The increase in beach tourism has led to pressure on this primary tourism asset, threatening the associated economic, recreational, natural, aesthetic and cultural resources of the destination. Currently, the focus of beach management is on meeting the wants and needs of the consumer and not on sustainability of safety.

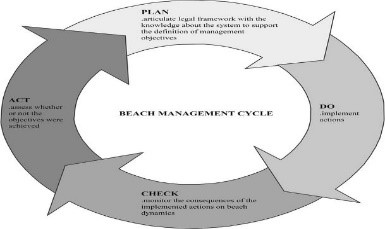

Beach managers have been criticized for not addressing the complex ecosystems they supervise. In some countries beach management ignores the physical, environmental, social and economic aspects of this unique real estate although it is the responsibility of these individuals to preserve and organize the natural environment while meeting the needs/wants of tourists. The task of maintaining natural beach systems while limiting activities (when curtailment is in the best interest of the environment) is not easy as it impacts directly on the revenue stream of the destination or hotel and frequently steps on biased political, governmental and business interests.

User Profiles

In order to have successful beach management it is advantageous to determine who uses the beach and the tourists’ motivations and interests as perceptions of a destination vary according to countries of origin, and age. The first step is to ascertain the concerns of the various user groups and then establish campaigns focusing on the short- and long-term impact of their behavior on the environment. The objective is to design a marketing effort that will establish a balance between user demands and the need to protect the beach ecosystems – engaging the beach user as a participant (a co-manager) in the stewardship and responsibility for protecting the beach ecological community.

Travelers who avoid risk are less likely to visit public spaces such as beaches and more likely to cooperate with government recommendations, adopting health-protective behaviors. This does not mean visitors will avoid beaches but rather they will select areas that are more remote, have less density and considered more exclusive. Active beach lovers may underestimate the risk of following their muse. This may occur because they are voluntarily taking the risk and therefore optimistic about the outcome, or, having no direct experience with the virus, are overly confident about their own personal health and the well-being of their friends and family and, in addition, outdoor spaces are perceived to be benign and therefore beaches are safe.

Fragile Ecosystem

Almost overnight, the most popular beaches on the planet were emptied by the advance of COVID-19, providing a short-term positive impact on the coastal environment while, at the same time the virus presented new threats. In order to avoid crowds many visitors defaulted to rural and natural beaches that may have a more delicate ecosystem and/or be more dangerous to swimmers and surfers because of tides, the absence of life guards or the lack of other public facilities such as rest rooms, parking, cleaning and safety services.

Environmental decay on beaches is a real possibility as the potential wastewaters can be infected by the virus and this possible contamination is of critical consideration to developing countries. Viruses can maintain their infectious capacity in water for prolonged periods, destroying the aquatic environment via sewage discharges.

Solid particles are suspended in water and sand and if countries do not treat their raw sewage before it is released into rivers, streams and oceans, fecal transmission from COVID-19 carriers is a real possibility. Swimmers, divers, and beach visitors can get infected through ingestion, inhalation, or skin contact of these particles. Even in countries with sophisticated monitoring programs the concentration of microorganisms from fecal pollution frequently surpasses the maximum permitted thresholds after rainy days when rainwaters mixed with untreated or partially treated sewage enters the sea.

Another environmental consideration for government and private sector leaders, including local authorities and beach managers is the impact of the chemicals used in large quantities to disinfect public spaces. The substances used to inactivate the virus can also affect marine organisms when transported to the ocean via sewage and rainwater drainage systems. The chemicals can cause death and destruction of algae, fish, mollusks, starfish, shrimp, etc. and be harmful to swimmers and beach visitors.

Related to these concerns is the increased use of protective apparel (i.e., gloves, masks) that may be inappropriately disposed and end up transported to the sea by wind or rainwater. In coastal areas without good rainwater treatment, potentially contaminated items can end in the sea or washed on to beaches presenting a hazard to marine organisms including crustaceans, mollusks, birds, turtles and fish who ingest the microplastics from degraded synthetic material.

Guard the Beaches

Beach-goers and beach managers require a new approach to safety and security in combination with environmental safeguards if these spaces are going to remain and/or return at sustainable levels. Ideas for beach safety include beach booths to isolate user groups from each other (Santorini, Greece); however, because of high levels of UV light, saltwater spray and significant temperature changes increase the likelihood of shattering, fogging or losing transparency, so – this idea is not gaining traction; another idea presents social distancing based on taped circles to demark spaces.

Although a visitor appears COVID-19 free, he/she could be transmitting the virus to others and in order to ensure social distancing many beach managers have closed toilets to minimize the risk of skin contact with potentially infected surfaces. A wide range of other facilities are also closed (food/drink kiosks, showers), including the removal of chairs and lounges. Beaches with wooden catwalks for visitors are recommending two lanes separated by at least a 6-foot gap to limit close contact with others.

Beach Management

The management of the beach ecosystem has been overlooked although it is a major factor in the reason’s travelers select a destination for domestic and international holidays. For locales concerned with beach tourism sustainability:

1. Public and private sector leaders must begin to identify and catalogue all beaches in their locale, documenting current conditions and determining what needs to be done to reach acceptable tourism levels, short and long-term.

2. Then it is necessary to identify the men and women responsible for maintaining this important natural resource.

3. Does beach management become the responsibility of the hotel owner/manager, a government agency, a mix of private/public stewardship?

4. Who is responsible for solid-waste management; how will this person/agency be held accountable for keeping the water clean and sanitary for public use?

5. What cleaning schemes are being used and are they environmentally friendly and safe for swimmers, surf-boarders, beach-goers and marine life?

6. Who is daily responsible for keeping the beaches clean and safe?

7. Who provides surveillance for these vulnerable spaces?

8. Who supplies and maintains the signage providing relevant information to visitors and local residents?

9. Who is responsible and accountable for environmental education programs?

10. Who secures and maintains water and health-related certification?

11. Who decides and maintains construction and maintenance of beach access?

12. Who decides and maintains beach infrastructure including lifeguard towers, toilets, showers, parking lots, food kiosks, information desks, hours of operation, police/security schedules, health, safety and accident response teams?

13. Who pays for all of the services required to develop and maintain a beach?

Cannot Be Replaced or Duplicated

Before COVID-19, the tourism industry did not consider the idea of beach management a top priority. Now this delicate bionetwork has become a focus and demands immediate attention. Beach inventory and operational managers with a unique skill-set are critical to develop and maintain this important component in the tourism space. Solid waste management has not, in the past, included biologically infectious waste such as masks and gloves. This new scenario, with the requirement to wear a mask in public spaces includes beaches. The challenge is to make sure this waste is disposed of correctly because of its environmental impact on people and marine life.

How clean is clean? COVID-19 raises more questions without offering any correct answers. How the virus spreads through sea and fresh water and sand, and how to keep the environment safe and clean is a function of humans and chemical products (i.e., bleach) and requires consideration as well as thoughtful and intelligent responses.

Beyond safety from crime and mischief, beach surveillance now includes the need to monitor the carrying capacity of beaches and social distancing. Some destinations are using drones and refined counting systems to keep everyone safe while others are trusting tourists to “do the right thing.”

Beyond Open/Closed, beach signage is now important as it must include messages about the correct use of masks, walkable, rest, and social spaces; social distancing; visitor numbers, etc.

Web and app developers have designed mobile applications that allow beach users to reserve their spaces or provide real-time information about beach capacity. In South Korea the app generates a QR code that allows beachgoers to be contacted if there is a COVID-19 outbreak associated with a beach they visited.

Caribbean Vulnerable

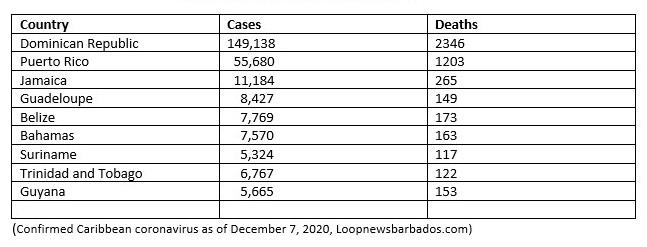

The economy of the Caribbean region is dependent on tourism and over 55M visitors selected this locale for holidays in 2019. With the increase in visitors is the corresponding increase in risks associated with health, safety and security on local populations. The region has been vulnerable to H1N1, zika, norovirus, measles and, currently, COVID-19. Unfortunately, the health monitoring systems have focused on local residents and the concept of monitoring the health of visitors is a new direction for the tourism industry.

The region is also deficient in food and environmental sanitation training and other safety/security measures and there is little integration between the tourism industry and healthcare providers and related services. Because of these gaps in protocol, there have been disease outbreaks, food safety issues, and environment sanitation challenges that have the potential for seriously damaging and/or destroying the entire tourism industry. The region needs a system to monitor the health and well-being of travelers and local residents, providing real-time information and responding quickly to prevent and/or control health related emergencies.

Focus on Diversification

Destinations that are one trick ponies, relying almost exclusively on sun, sea, and sand for their economy could consider the pandemic embargoes as the perfect moment to diversify their economies; however, there appears to be little or no interest in this endeavor. In spite of the global increase of COVID-19 cases and deaths, the uptick in air travel to beach destinations is very seductive as this revenue stream permits a continuation of “business as usual.” For those destinations attempting to straddle both sides of the fence – permitting entry to global travelers seeking a holiday while keeping their own populations free of COVID-19, the result ends in confused messages, adding to the pandemic anxieties of potential visitors.

The public and the private sectors have leadership vacuums. The men and women in these positions are not taking the time or making the effort to review the risk perceptions of tourists in combination with environmental considerations and management strategies with the objective of creating a sustainable tourism product that will work today and tomorrow. Another gap in the open borders approach to visitors is the lack of consideration for the potential of visitors polluting the waters and sand with COVID-19 as sand, and sea are viable routes of virus transmission and the use of chemical disinfectants on the destruction of the marine environment and on bathers has not been part of their calculations.

We can hope (and pray) that enlightenment combined with economic necessity and long-range planning will ultimately transform the future for island destinations.

© Dr. Elinor Garely. This copyright article, including photos, may not be reproduced without written permission from the author.

#rebuildingtravel