“Do not get very sick in New York City… so sick that you require emergency care,” warns Dr. Elinor Garely. She suggests that “Hospitals look to the hospitality industry for guidance and direction if they have an interest in turning a sick patient into a healthy visitor.”

- New York State research data shows that over 4 million people make approximately 7 million visits yearly to hospital emergency departments.

- Assumptions, based on many television ER medical series, are an outdated understanding of how emergency medicine is practiced in New York.

- Hospitals should look to the hospitality industry for guidance and direction if they have an interest in turning a sick patient into a healthy visitor.

Business travelers and tourists frequently get sick while visiting new countries and new cities. A telephone call to the front desk of a hotel, or an urgent call to a friend or colleague may not provide a healthcare provider fast enough to deal with the immediate medical issue. What to do? Currently, the quick response is to head directly to Urgent Care or the ER/ED section of the nearest hospital.

eTurboNews.com reporter, Dr Elinor Garely, a native New Yorker, recently experienced an aftershock from her second COVID vaccine, and has spent the last 6 weeks running to doctors and ER facilities finding the huge gaps that exist between expectations of medical attention in Manhattan and the reality.

Dr. Garely shares with us her personal experiences and observations as she addresses the chaos of the Manhattan emergency care realities with the hope that visitors to the city will find a pathway to wellness and avoid (or sidestep) a few of the biggest potholes on their way to recovery.

Garely finds that “It is unfortunate that the hospital industry does not spend more time and effort investigating the protocols and procedures of the hospitality industry where the guest is the focus of services and less time on attempting to maximize a fragile and faulty revenue stream.”

Here is her story in her own words.

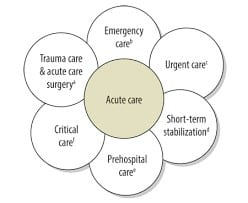

Hospital-based emergency care is the only medical treatment to which Americans have a legal right, regardless of their ability to pay.

The Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA) was passed by Congress in 1986 and requires hospitals and ambulance service to provide care to anyone needing emergency healthcare treatment regardless of citizenship, legal status, or ability to pay. The legislation sets forth no provisions for reimbursement.

ER/ED as a destination

New York State research data (2017-2018) records that over 4 million people make approximately 7 million visits yearly to hospital emergency departments (ED); however, they do not result in a hospital stay. A deep dive into the primary reason for these ED visits indicates that many could have been assisted in a different, less costly primary or preventive care setting. The absence of alternatives has led to US$8.3 billion in additional costs for the industry (Modernhealthcare.com). It has been found that 60 percent of the visits (4.3 million) centered on 6 chronic conditions: asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, heart failure, hypertension, and behavioral health conditions such as mental health or substance abuse issues.

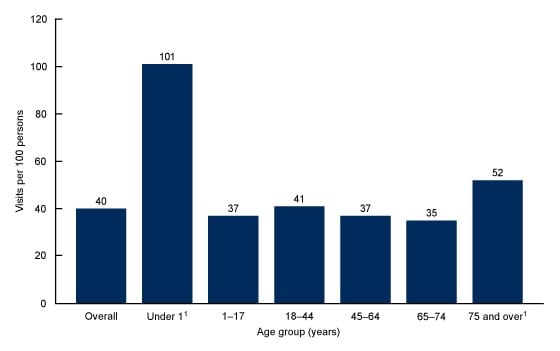

On a national level, 130 million people in the USA visited an ED facility with 35 million visits related to an injury. Of the emergency department visits, 16.2 million led to in-hospital admission with 2.3 million resulting in admission to critical care units. Of the patient visits, 43.5 percent were seen in less than 15 minutes with 12.4 percent resulting in hospital admission and only 2.3 percent ending in a transfer to a different (psychiatric or other) hospital (2018 NHAMCS Public Use File).

A 2018 research study found that the primary group visiting an ED are under the age of 1 year, with 52 percent aged 75+. The ED visit rate for females was 44 visits per 100 persons, higher than the rate for males (37 visits per 100 persons). In 2018, the ED visit rate for non-Hispanic black or African American persons was 87 visits per 100 persons, higher than rates for persons from all other race and ethnic groups. The ED visit rates for Hispanic or Latino persons (36 per 100 persons) and non-Hispanic white persons were 35 per 100 persons.

The ED visit rate was highest for patients with Medicaid (97 visits per 100 persons) with the lowest rate for patients with private insurance (23 visits per 100 persons) (National Center for Health Statistics, Division of Health Care Statistics).

Antiquated systems

Although most hospital types are affected, the crowding problem is particularly severe in urban and teaching hospitals. A 2010 survey by the American Hospital Association revealed that more than 50 percent of surveyed urban and teaching hospitals had EDs that were at or over capacity. Exacerbating the problem is the alarming trend of a decreasing number of EDs and an increasing number of ED visits.

Adverse encounters

Although all EDs struggle with issues of overcrowding and stretched staff-to-patient ratios, under-funding, resource constraints in conjunction with inherently high-risk populations and high-risk diagnostic errors create an environment designed for disaster.

EDs are not the final destination for most patients but rather a pause on the way to another deposition (i.e., home, a specialized unit, inpatient bed) resulting in the availability of emergency beds often at the mercy of the limited resources of other hospital departments and other units of the health care system.

Hallway medicine: Boarding

A commonly cited cause of ED inefficiency is “boarding” (aka Admit Holds) which occurs when a patient has been admitted to the hospital but is waiting for an inpatient bed to become available for transfer. In the meantime, the patient occupies an ED bed that is needed by a patient still in the waiting room. Because of hospital inefficiencies, patients are “boarded” in hallways or unlicensed care areas to make room for new patients in the waiting room that require to be seen and evaluated. “Hallway medicine” is substandard medical care but has become a reality of life in America’s EDs.

Some research suggests that the biggest culprit is too few beds, along with shortages of doctors, nurses, and medical equipment needed to care for each admitted hospital patient. This bottleneck at the gateway of American hospitals has led to as many as two-thirds of all emergency room patients, sick enough to be hospitalized, sitting in waiting rooms, “boarding” on stretchers in ED bays, or dozing in chairs in the hallways until a bed becomes available. With patients crammed into every available space, ER nurses and other healthcare providers quickly become overwhelmed, leading to fatal medical errors and significant delays that affect the outcome of patients who have suffered heart attacks, strokes, or infections.

Waiting and waiting

A driver of growing and high wait time is how many patients show up for treatment. Many are referred to the ED department by outside physicians. These referrals could occur because physicians are not sure if they can provide complete care, or because their schedule is too tight to see patients quickly. One study found that about half of nonemergent patients contacted another physician first and 70 percent of them were told to go the emergency room.

Adding to the ED load is the reality that outside physicians often lack admitting privileges to hospitals. When a patient needs to be admitted as an inpatient, but the provider cannot admit them directly, they send the patient to the ED for admission. A report from the American College of Emergency Physicians suggests that 70 percent of hospital admissions come through emergency rooms and it is increasing.

Success is an illusion

A successful ED depends on the amount of time patients spend from entry to leaving the facility (LOS – Length Of Stay). LOS also affects patient behavior. Poor wait times encourage Leaving Without Being Seen (LWBS) and Discharge Against Medical Advice (DAMA). LWBS is often the benchmark for the EDs. These rates can go as high as 20 percent in some cases. Studies show that DAMA has had a steady 2 percent increase over the last decade. Administrators have to juggle limited beds, equipment, and staff shortages while dealing with patient expectations. Emergency management is vital and frequently fails.

Non-responsive

The ED system needs to be more responsive to patients, taking into account how they decide when and where to seek care. Primary care clinics must be better rewarded for providing a lower-cost alternative to ED use and for preventing emergency situations from developing. Without stronger incentives and higher payment rates, there will be fewer sources of primary care in the future.

Becoming an ED patient

I live in Manhattan and had been using the same primary care doctor for decades. I always assumed that if I ever was in need of emergency care, he would be there to throw me a life preserver. Over the telephone or Telemed I would explain my symptoms. Having my records at his fingertips he could review my medical history and provide immediate assistance, recommendations, access to drugs, admit me to a hospital when necessary, and – in general – get me back on the road to feeling good.

Sadly, my assumptions, based on many television ER medical series, were an outdated understanding of how emergency medicine is practiced in New York, and a seriously flawed estimate of how sick I was, placed me in a level of medical hell I had never imagined, heard of, experienced, or anticipated.

One moment I was contemplating a new hair color and style, and the next minute I am rushing back and forth to the toilet with uncontrollable diarrhea, to be followed, weeks later, by overwhelming constipation, all leading to multiple admissions to hospital EDs (New York’s Mount Sinai and NYU’s Langone).

Path to sick

How did this weird illness happen? Where did it come from? One GI doctor thinks that it happened as a result of Moderna Vaccine #2. Other health care professionals think it was sparked by drinking 45 ounces of Volumen, prescribed for patients on their way to an MRE test. Whatever the cause, no one has offered a sold scientific or medical theory to solving the problem except by throwing Imodium at it.

As my medical issues turned into a crisis, I tried to reach my primary care physician on the telephone. When I was able to get through the voice prompts, I landed at the office of a telephone message service, speaking to an arrogant woman who informed me that my doctor was not available. If this call was truly an emergency, I could leave a message and the on-call doctor would circle back. With no other options, I left my information and then waited and waited and waited. When I had just about run out of patience and seeing my toilet paper supply depleted, I finally heard the phone ring. I picked up the telephone and got to speak to a doctor. My primary was unavailable, but she would try to help. I explained the symptoms, reviewed my medical history, and was told to go to the ER room of a hospital or Urgent Care. She repeated my choices and wished me luck. There was no way she was going to offer an opinion, a diagnosis, a remedy, or offer an office visit. I could head to an emergency room, critical care facility, or deal with the problem – she was off the case.

In Manhattan, if you have a medical emergency, you do not get to link to your primary physician. You are not directed to rush to their office or to meet them at the nearest hospital where they will guide you through intake procedures, process you into an empty hospital bed, or, in many cases, even visit with you after you have been admitted. There is one way to get into a hospital bed, and the only route is through the Emergency Department.

Unfortunately, in 2021, the ED is not for the exclusive use for people with emergencies. This space is frequently the first point of contact for many patients with minor ailments who use the same space and services as those patients with true emergencies. To be politically correct, each person expects and deserves treatment with some degree of immediacy; however, the mix of emergency and non-emergency situations complicates the process and wreaks havoc on available procedures and limited resources.

EDs: Not created equal

Mount Sinai ED, hell on Earth

In the last two months, I have had up close and personal encounters with the EDs of two major medical institutions in New York City, Mount Sinai, and NYU Langone. Because Mount Sinai has used Dante’s vision of hell as its model, I will not linger on the thousands of horrors waiting any person who is brave enough to enter this facility.

From hundreds (perhaps thousands) of patients waiting for medical attention, stacked on gurneys parked closer together than sardines in a can, to people so sick they are vomiting into bed pans and screaming with pain at their top of their lungs, almost everyone is ignored by the few health care professionals available to deal with the sick and injured at Mount Sinai.

Doctors are not readily available to anyone! Forget the doctor/nurse images that cross television screens from Chicago Med and Grey’s Anatomy; the belief we have been consuming about doctors, nurses, and hospital administrators are pure fiction and have a lesser degree of authenticity than Goldie Locks and the Three Bears.

At Mount Sinai, sanitation is a concept that appears exclusively in a dictionary. The very basic supplies, from toilet paper to handi-wipes and feminine hygiene products – all supplies are kept out of sight (if they exist at all). Doctors make quick fly-bys – searching for patients by yelling their name and waiting for the sick or injured person to raise a hand and identify themselves. Sometimes the medical staff has to climb over and around the stacked gurneys because the person they are seeking is four rows in the rear, and they have to fumble around the myriad of other patients desperately seeking to talk with a doctor or a nurse (think of a war zone with causalities stacked after a bomb explosion with each solider reaching desperately for attention). I have visited hospitals in emerging countries, and the Mount Sinai experience ranks below medical care available in the least-developed Caribbean countries, India, or South Africa.

Patients are left to their own devices for hours and days without food, water, sanitary products, medications, or updates on their condition, combined with long walks to toilets. If you do not have a cell phone, you can forget about communicating with anyone. If you do not have a charger and back-up energy, forget about Wi-Fi and telephone access as there are no charge stations near the gurneys and the computer terminals are for staff only.

After almost 10 hours of being tested and poked by a myriad of unnamed and unknown medical people, I was finally informed that because of the severity of my condition, I would be admitted to a hospital bed. Hours passed and the only movement was by a nurse who moved my gurney ever closer to others as there was a surge in ED patients and there was no more available space. Forget about the 6 feet of distance for COVID precautions, forget about updated HVAC systems, COVID was not even an after-thought in the Sinai emergency environment. When I finally found a nurse who would talk with me (and stop staring at a computer screen), I was told that I could wait up to 72 hours to actually get a bed in the hospital (and this was on a good day). I did try to contact the gastro doctor who referred me to the Sinai ED – but he did not respond to emails and there were no other ways to contact him.

I was too sick, too hungry, too dirty, and too angry to remain at Sinai – so I checked myself out of the hospital and was determined to deal with my medical issues at home. I had to hunt down my nurse (again) and convince him to take his eyes off his computer screen to tell him I was leaving. He contacted a doctor in the gastro department because paperwork was required prior to release. Minutes/hours later a doctor finally arrived at my gurney. Once he quizzed me on my name and date of birth, he wanted to know why I was in the ER and the name of my doctor! This “doctor” had no idea who I was and could care less. The only interest from this fellow? Get the paperwork signed, get the nurse to take out my IV tubes, and send me on my way.

I survived Sinai ER, but memories of the nightmare are etched on my brain forever. My personal recommendation: do not, under any circumstances, go to Mount Sinai for medical emergencies.

Through good fortune I was able to hail a taxi (I had no charge left on my cell phone and no hospital address, so Uber and Lyft were out of the question). I went home, took a shower, tried to sleep, and when I awoke, tried to figure out what to do next.

Account continues

I was unfortunately not on the road to a miraculous cure or immediate recovery, and my condition deteriorated as the hours moved into days and weeks. Through dogged perseverance I pushed my way through the NYU Langone physician blockades, finally finding doctors who would accept new patients with appointments available a few days/weeks and not months in the future. Through luck I found a gerontology physician who had the presence of mind to schedule a sonogram and this test validated my condition, giving other doctors a pathway to a solution. This was not a smooth sail.

New York University, Langone ED

My health was not improving. Tests displayed the fact that there was nothing I could do to improve my condition if I stayed at home, I had to go back to the hospital. Well, not exactly to the hospital, I had to go back to ER. This time I went to the ER department at NYU Langone, and the difference between this facility and Mount Sinai is the difference between life and death.

The best time to arrive at the NYU ER is between 8-9 AM. Patients from the previous day have either been sent home or been admitted to a hospital bed. The new shift of health care professionals is just arriving, so they are awake and have the energy to assess patient conditions.

Where are the doctors? I really have no answer to this question! The first time I was at the NYU ED I was quickly seen by a doctor and an intern. This “luxury” never happened again. Doctors are few and far between. On one ER visit, I never saw a doctor (at least no one I remember as being a doctor). The people interacting with patients are either nurses or physician assistants.

Patient processing

Patients arriving at the NYU Langone emergency entrance are processed through a system that requires name, address, identification, and insurance information (if you are not in their database), plus a quick summary of the reason for being at the ER and an evaluation of pain level, ending with the issue of a wrist ID bracelet with name, date of birth, and date of admission.

Although the pain level is questioned, it does not appear to impact on the speed of talking with a doctor. The last time I was at the ER, my pain level (on a scale of 1-10) was 15 (actually closer to 50)! I was barely functioning at this level of pain, but it did not get me through the entry process any quicker nor did it get me an instant conversation with a doctor. The only acknowledgement of the pain was the opportunity to be brought to an ER section and placed on a gurney along with wheelchair transportation.

While the intake staffers are friendly, be prepared for personal conversations to be completed before your medical needs are addressed. After a few delays, I completed the intake protocols (blood pressure, temperature, name, address, age), and I was moved from reception to an empty bay, placed on a gurney, and left on my own. Although I was screaming at the top of my lungs about the pain, I did not see a nurse, PA, or doctor for what seemed to be hours. The curtain surrounding the bay was closed, and I was left to scream and scream – until I either fell asleep or had no energy left for screaming and could only whimper.

Patients in ER rooms are assigned a nurse, and this is the only professional with whom communication is permitted. Unfortunately, there is no way to contact the assigned nurse. There are no emergency buttons, bells, or electronic devices – nothing! If the nurse does not come to see you – the only way to get assistance is by standing in the hallway outside the bay, and attempt to find the nurse by scanning people who are sitting behind computers or entering/exiting other bays and screaming their name. Sometimes it is possible to ask another nurse to find yours, but this gesture is not appreciated. Whether it is by choice or policy, the only person “authorized” to respond to your needs, is the assigned nurse.

Blood tests are popular in ER rooms, and, within minutes test results show up on the NYU Langone MYCHART without explanations. Should I worry if the tests indicate I am above or below “normal range”? Short of taking the medical term for the test and doing a Google search – there is absolutely no way to know if the result of the test is good or bad news. Question a nurse or doctor on the tests; the quest for additional information is ignored. Of course, if you do not have a cell phone or tablet – there is no way to access any of the information.

Not in the 21st century

As compared to Mount Sinai, the ER spaces at NYU Langone are clean; however, requests for cleaning one of the few mixed sex bathrooms took hours although feces, blood, and other unidentified liquids glimmered brightly on the floor making the space unsanitary and dangerous for slips and slides.

The toilet facilities are poorly designed and require manual cleaning. There is no counter space to place a handbag or a sanitary product. If attached to an IV, there is almost no comfortable or efficient method for using the toilet, keeping the hospital gown covering a few body parts and getting personally clean enough to leave the area. An architect and/or interior designer along with a sanitary engineer should be immediately hired to design this necessary amenity so that it is efficient, effective, and sanitary.

For patients fortunate enough to earn a private bay, the space and the gurney need a new design. To use the faucet and a wash basin, the patient has to walk/crawl from the gurney to the water source. Unless you have the forethought to bring a pair of disposable flip flops to the ER, getting from the bay to the toilet to the water – all the time attempting to keep the hospital gown covering your ass and not displaying both the left and right breasts – is more complex that winning a game of chess.

Another redesign necessity is the hospital gown. Where is Vera Wang or Ralph Lauren when you need them? Heading to the ER – pack your own cotton gown and plastic/disposal flipflops. PJs will not work as the medical staff may need to access parts of your body that are hard to reach when wearing shorts or pants.

Survival of the fittest

Fortunately, I have landed at the NYU Langone Women’s Center that is staffed by intelligent and caring women doctors. My GI doctor and her team of nurses and administrators actually respond to questions on meds and after-visit concerns.

Change is beyond necessary – it is critical. Without embracing 21st century technology, robotics, and anti-microbial furniture and materials, along with an evaluation of the antiquated system with an appreciation for the efficient and effective changes being introduced by the hospitality industry (especially airports), the ED system will implode. I shudder to consider a major explosion or terrorist attack in Manhattan as the ED hospital system would be unable to deal with an enormous surge in causalities.

To change the ED systems and protocols it is necessary to require improvements to the primary care system which needs to be more responsive to patients, taking into account how they decide when and where to seek care. The opportunities for private doctors to be engaged in the ED process also requires a review.

Private physicians and primary care clinics must be better rewarded for providing a lower-cost and yet effective and efficient alternative to ED use and for the prevention of emergency situations from developing. Without stronger incentives, higher payment rates, and the acceptance and inclusion of new technology and management, the ED sector of American healthcare will continue to sink lower and lower to the point of no return.

© Dr. Elinor Garely. This copyright article, including photos, may not be reproduced without written permission from the author.