The French have spent many marketing dollars conditioning us to equate Champagne with good times, simultaneously encouraging us to believe that all sparkling wines are French. Results? Champagne has become a word that is ubiquitous. If we have an urge for a glass of sparkling wine our brain immediately latches onto the word Champagne, and we place our order with the bartender or the manager at the wine shop.

In reality, in addition to France (producing 550 million bottles), we have choices that include Italy (prosecco – producing 660+/- bottles), Germany (producing 350 billion bottles), Spain (Cava. +/- producing 260 million bottles), and the United States (producing 162 million bottles) (forbes.com). We have come to realize that sparkling wine is terrific when we are happy, wonderful when we are sad, necessary when we have been fired, and just what we need when we get a positive on an Omicron test.

The universal appeal for sparkling wine has increased production by 57 percent since 2002 and world production accounts for 2.5 billion bottles which is slightly less than 8 percent of the world’s total wine production of 32.5 billion bottles. Slowly increasing is the demand and production of sparkling wines are Australia, Brazil, UK, and Portugal.

Sparkling Wine in Spanish? CAVA

CAVA means “cave” or “cellar” where, at the beginning of cava production, the sparkling wine was made and aged or preserved. Spanish winemakers officially used the term in 1970 to separate the Spanish product from French champagne. A cava is always produced with the second fermentation in the bottle, and with at least 9 months of bottle ageing on the lees.

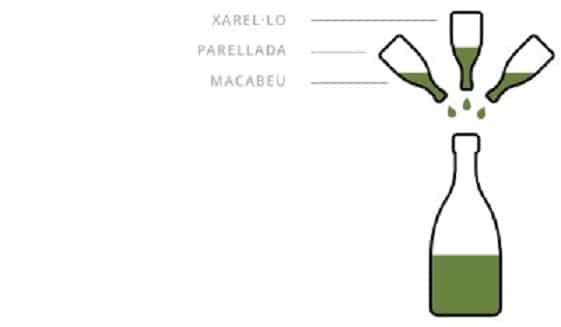

Don Josep Raventos, a descendant of Don Juame Codorniu (founder of Cordorniu – one of the largest cava producers in Spain), made the first recorded bottle of Cava in the Penedes region, Northeastern Spain. At the time, phylloxera (louse-like insects that destroyed vineyards lusted for red varietals in Penedes) left the region with only white varietals. At this time, the white varietals were not commercially viable when made into good still wines. Learning of the success of French champagne, Raventos studied the process, adapting it to create the Spanish version of champagne using Methode Champenoise from the available Spanish varietals Macabeo, Xarello, and Parellada – giving birth to Cava.

Ten years later, Manuel Raventos began a marketing campaign throughout Europe for his Cava. In 1888, Cordorniu Cavas won the first of many gold medals and awards, establishing the reputation of Spanish Cava outside Spain.

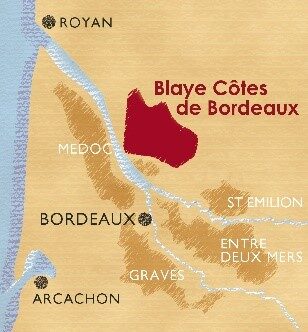

Marketplace

Spain is the third largest exporter of sparkling wine, slightly behind France, with exports going primarily to the United States, Germany, and Belgium. As the iconic sparkling wine of Spain, Cava is made in the traditional method of French Champagne. It is largely produced in the northeast sector of the country (Penedes area of Catalonia), with the village of Sant Sdaurni d’Anoia the home to many of the largest Catalan production houses. However, producers are dispersed throughout other parts of the country, especially where Cava production is part of the Denominacion de Origen (DO). It can be white (blanco) or rose (rosado). The most popular grape varieties are Macabeo, Parellada and Xarel-lo; however, only the wines produced in the traditional method can be labelled CAVA. If the wines are produced by any other process they must be called “sparkling wine” (vinos espumosos).

To make rose cava, blending is a NO NO.

The wine must be produced via the Saignee method, using Garnacha, Pinot Noir, Trepat or Monastrell. Besides Macabeu, Parellada and Xarel-lo, cava may also include Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Subirat grapes.

Cava is produced in varying levels of sweetness, ranging from dry (brut nature) through brut, brut reserve, seco, semiseco, to dulce (the sweetest). Most cavas are non-vintage because they are a blend of different vintages.

Cava Marketing Challenges

Why does the word Champagne flow so naturally from our lips, and Cava may not be in our wine lexicon? The sparkling wine from Spain is positioned in a saturated sparkling wine market, and suffers from an inadequate marketing budget. The Italians have spent billions of dollars and Euros getting Prosecco to be part of our everyday jargon, and France has been promoting Champagne since 1693 (when Dom Pérignon “invented” Champagne,

Knowledgeable wine consumers appreciate the qualities inherent in Cava: hand harvest, gentle pressing of whole bunches in small high surface area presses; extended lees aging in the bottle; hand disgorgement for premium cuvees; and loyally following traditional method practices. While the wine groupie knows, and appreciates the details, others who just “like wine,” perceive a sparkling wine that is

In-store shelf stockers also put Cava at a disadvantage, frequently shoving Cava in with inexpensive jug wines or cheap spirits. Higher quality cuvees (reserve, Gran Reserva, and Cava del Paraje) do not occupy a place in the wine buyers’ brain, or, if they do, it may be in the section of the brain called “budget,” forcing Cava to compete with English sparkling wine and even some inexpensive Champagne brands.

Cava is growing in popularity, and new rules have kicked in to maintain and increase quality creating the Regulatory Council of the CAVA Protected Designation of Origin. Starting in 2018, Javier Pages has led the organization while he is also the President of the Barcelona Wine Week (international Spanish wine fair).

New Rules

What will the regulations accomplish? The rules will enlarge the quality features of Cava and include all winegrowers and makers of the Designation of Origin (DO), increasing maximum origin, and quality.

If the Cava is aged longer than 18 months it will be called Cava de Guarda Superior, and made from grapes from vineyards registered in the Regulatory Board’s specific Register of Guara Superior, and must meet the following requirement:

a. Vines must be at least 10 years old

b. Vines must be organic (5 years of transition)

c. Maximum yield of 4.9 tons/acre, separate production (separate traceability from vineyard to the bottle)

d. Proof of vintage and organic – on the label

1. Production of Cavas de Guarda Superior (includes Cavas Reserve with a minimum of 18 months of aging; Gran Reserva with a minimum of 30 months of aging), and Cavas d Paraje Calificado – from a special plot with a minimum of 36 months of aging – must be 100 percent organic by 2025.

2. New zoning of DO Cava: Comtats de Barcela, Ebro Valley, and Levante.

3. Voluntary creation of an “Integral Producer” label for wineries that press and vinify 100 percent of their products.

4. New zoning and segmentation by Cava DO will appear on labels of the first bottles in January 2022.

Corpinnat. Wineries Fight for Freedom

Some Spanish wineries have left their DO, creating a single-member designation: Conca del Rui Anoia because they are dissatisfied with the Dos historical indifference to quality that is demeaning the brand. Corpinnat is a new name among high-quality, sparkling Spanish wines, and the founders have presented a plan to the Spanish Ministry of Agriculture for certification. When/if approved, it will be a dramatic overhaul of the Cava brand.

In 2019 nine wineries left Cava DO to form Corpinnat for fine sparkling wine. The wineries wanted to include Corpinnat with the DO but the regulatory board refused – so they left. The wine producers are interested in creating a wine with a focus on terroir. Unlike France, Spain does not have a terroir focused classification system, and small producers of quality wines throughout Spain have been asking for a change for years. Bulk producers who buy up grapes from anyone and anywhere in their very large geographically defined zone generate large quantities of cheap, headache inducing, industrial products, labeling it with the same DO, making it nearly impossible for small, terroir-drive estates to differentiate themselves.

Cava does not go through the same rigorous testing as Champagne.

This results in the reality that large producers of cava are able to produce large quantities of low-quality wine with the same classification smearing smaller producers of good quality wine with the same mediocre brush. The absence of control over quality has resulted in the reality that the once world-famous title of Cava has lost its prestige while the global market for sparkling wine booms. Cava has lost market share to prosecco, whose charmat method makes it inherently less expensive to produce.

Curated Cavas

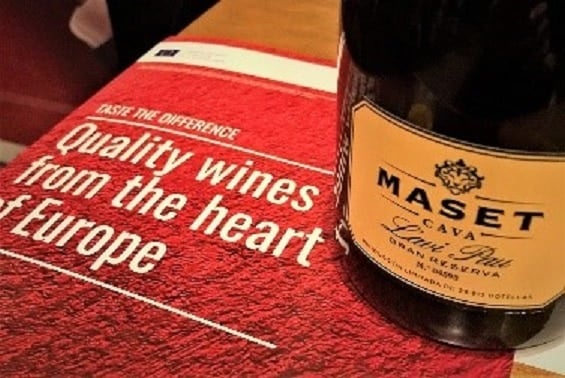

At a recent New York City wine event, sponsored by the European Union (Quality Wines from the Heart of Europe) I had the opportunity to experience a few Cavas. Of the sparkling wines available, the following were my favorites:

1. Anna de Codorniu. Blanc de Blancs. DO Cava-Penedes. 70 percent Chardonnay, 15 percent Parellada, 7.5 percent Macabeo, 7.5 percent Xarel.lo

Who was Anna and why place her name on a Cava? Anna de Codorniu is noted as the woman who changed winery history through her mastery, and elegance she pioneered the addition of Chardonnay varietal into the Cava blend.

To the eye, Anna presents a bright and energetic blonde hue with green highlights making it delightful to view for the bubbles are fine, persistent, vigorous and continuous. The nose is happy with a discovery of wet rocks, orange citrus, and tropical fruit linked to ageing aromas (think toast and brioche). The palate enjoys creamy, light acidity, and long-lasting excitement leading to a long sweet finish. Perfect as an aperitif, or with sauteed vegetables, fish, seafood and grilled meats; stands solidly alone or joined with desserts.

2. L’avi Paul Gran Reserva Brut Nature. Maset. 30 percent Xarel-lo, 25 percent Parelllada, 20 percent Chardonnay.

Paul Massan (1777) is memorialized in the L’avi Pau Cava, as the first in the family’s lineage. Old vines (20-40 years) are planted at low density at an altitude of 200-400 m above sea level. The wine ages in cellars 5 m below ground with a minimum ageing of 36 months.

The eye finds golden shades, and well-integrated bubbles while the nose is rewarded with very ripe fruit, citrus, brioche, and almonds. The palate discovers a dry, and creamy adventure that leads to a long, persistent finish with a sweetness suggestive of honey and crabapples. Pair with prawns and hot peppers or pour over oysters.

For additional information, click here.

This is a series focusing on the Wines of Spain:

Read Part 1 Here: Spain Ups Its Wine Game: Much More Than Sangria

Read Part 2 Here: Wines of Spain: Taste the Difference Now

© Dr. Elinor Garely. This copyright article, including photos, may not be reproduced without written permission from the author.