Wine grapes, not indigenous to South America, found their way to the region through the lens of European exploration and settlement.

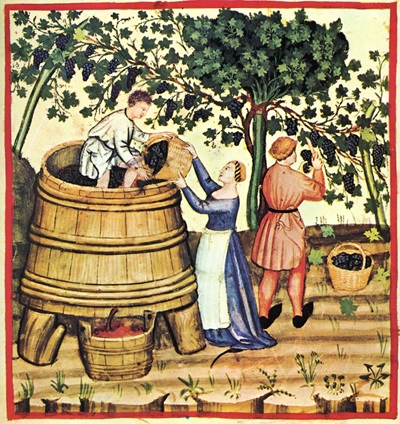

The intricate dance between European explorers, missionaries, settlers, and the indigenous populations marked the inception of viticulture in this part of the world.

Christopher Columbus’s 1498 exploration of South America‘s northern coastline triggered a surge of European investigation and colonization in the early 16th century. Spanish conquistadores, pivotal in introducing European plant species like wine grapes, often arrived via established routes in Mexico. Since 1524, Hernan Cortes had been cultivating wines in Mexico, and the Hacienda de San Lorenzo in Parras Valley stands as the first commercial winery outside Europe, persisting today as Casa Madero.

Missionaries, driven by evangelical pursuits and the Spanish quest for land and resources, fueled viticulture growth.

In the 1540s, Francisco de Carabantes planted grapevines in the Ica Valley, birthing Tacama, one of Peru’s oldest active vineyards. The 16th century saw significant milestones, including the planting of vines by Hernando de Montenegro and the establishment of the first winery in Argentina by Juan Cedron.

The mid-16th century witnessed English privateer Francis Drake capturing a ship laden with Chilean wines in 1578, marking a period of global demand for Peruvian wine. However, events in the region led to a decline in wine production by the end of the century.

Research indicates that in 1554, Spanish conquistadors and missionaries transported European Vitis vinifera vines to Chile. Juan Cedron, a Spanish missionary, journeyed to Santiago del Estero in northern Argentina in 1556, initiating Argentina’s first winery.

Bolivia, in 1560, became the next destination for grapevine planting by Spanish missionaries, introducing Criolla varieties and benefiting from the favorable high-altitude Andean climate.

Today, the South American wine industry is a cornerstone of the economies of Argentina, Peru, and Chile, contributing to employment, exports, tourism, and overall economic growth.

Leading Countries and Popular Varietals

Argentina and Chile dominate the South American wine market, accounting for over 80 percent of production. Brazil represents around 10 percent, with Colombia, Uruguay, and Peru also contributing.

Popular Varietals:

Argentina: Malbec (22 percent), Cereza (12 percent), and Bonarda (8 percent)

Brazil: Chardonnay, White Moscato, Glera; reds dominated by Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, and Pinot Noir

Chile: Cabernet Sauvignon (29 percent), Sauvignon Blanc (11 percent), and Merlot, Chardonnay, Carmenere, and Pais (8 percent each)

Colombia: Grapes from southern Italy including Nebbiolo, Nero D’Avola, and Zibibbo

Peru: Red wine grapes include Malbec, Cabernet Sauvignon, Tannat, Syrah, and Grenache; White grapes include Muscat, Sauvignon Blanc, and Torrontes

Uruguay: Tannat (36 percent), Merlot (10 percent), Chardonnay (7 percent), Cabernet Sauvignon, and Sauvignon Blanc (6 percent each)

Diverse Grape Growing Conditions

South America’s grape growing conditions, spanning 15-40 degrees south latitude, rival renowned Northern Hemisphere areas. Unique conditions in Argentina’s Mendoza Province, with vineyards at 2,800 to 5,000 feet above sea level, and Chile’s coastal regions influenced by the Humboldt Current, showcase the diversity.

Climate Challenges and Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism Impact

The South American wine industry confronts climate change challenges affecting grape ripening, water stress, and disease outbreaks. The European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) poses a significant threat, potentially impacting competitiveness and profitability.

Producers are adapting with resilient grape varieties, water conservation through drip irrigation, and embracing renewable energy sources.

Water Scarcity and Glacial Changes

Water scarcity, linked to climate evolution and population growth, poses a major issue in Chile and Argentina. Glacial losses since the 1950s, coupled with uncertainties in water availability, raise concerns for arid/semi-arid viticulture regions.

The main source of water comes from winter-accumulated snow melt and glaciers that feed rivers and water tables. In the last few decades, glaciers throughout the Andes have been experiencing important losses. Since 1950 a major sustained increase in the rate of glacier ablation has been observed. This has been consistent with other climate changes observed in the regional subtropical troposphere and the lower stratosphere at mid to high latitudes. There has also been substantial glacial mass declines and even the total disappearance of glaciers as a result of climate change with uncertainties in the precipitation of water availability in many arid/semi-arid regions dedicated to viticulture in southern South America. Glaciers may even disappear.

Ozone depletion in the Southern Hemisphere adds another layer of complexity, potentially modifying wine flavors.

In navigating these challenges, South American wine producers are compelled to adopt sustainable practices, reduce carbon emissions, and explore collaborations to mitigate CBAM’s impact.

Exports

Exporting wine is a very complex process due to trade regulations, tariffs, and labeling requirements. South American winemakers often encounter barriers when trying to access the international market, limiting their export potential. In addition, the region is noted for economic instability which impacts production costs, pricing, and profitability of wineries. Fluctuations in currency values and inflation affect both domestic and international sales.

Challenges

Infrastructure and technology are lacking in many wineries which frequently leads to inconsistency in the quality and quantity of locally produced wines. Climate change poses a threat to all South American winemakers Those who accept the challenge, adapting practices and procedures ace increased risks from unpredictable extreme weather events.

Consumer Requests

Consumers are voting in favor of sustainably produced wine and while many local winemakers are adopting sustainable practices, it takes time and financial resources to build a reputation for eco-friendly production methods.

South American winemakers have traditionally focused on a limited number of grape varietals, such as Malbec and Carmenere. Although diversification is an option, many traditional winemakers are not anxious to embrace hybrids.

It is challenging to build effective and efficient distribution channels and to ensure consistent availability of wines in key markets. Distribution challenges require significant investments and the resources may not be readily available to the South American winemaker.

To add even more complexity to the industry, consumer tastes and preferences are constantly evolving, and adapting to these changes in market demands is expensive, time-consuming, and frequently risky.

Despite these challenges, the South American winemakers have made substantial strides in recent decades with some regions gaining international recognition for their high-quality wines. By addressing issues, investing in technology and infrastructure, diversifying their product offerings, and focusing on sustainable practices, South American winemakers are likely to increase their level of success in the global wine industry.

© Dr. Elinor Garely. This copyright article, including photos, may not be reproduced without written permission from the author.

![[part-3] 2025 Surgeon General’s Advisory: Paving the Way for Healthier Wine and Spirits Choices](https://inmypersonalopinion.life/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/wine-cancer-3.jpg)