Frequently, when I enter a neighborhood wine shop in Manhattan, I am stopped from browsing by aggressive salespeople which is counterproductive if the store owner is interested in increasing bottom line profitability.

When I walk into a shoe store, I am given lots of time to look at each shoe on display, turn it over to check the price, select the shoe(s) that look promising, and then approach a salesperson. When I walk into a sandwich shop, I have all the time in the world to look at the displays, read the on-wall menus, watch what others are ordering, and then, when I am ready, join the line, and place my order.

Unfortunately, when I amble into a wine store, I feel like I am entering a used car-lot. I am quickly hustled by the staffer, asked what kind of wine I want, ushered immediately to the section and “he” hovers while I scan the labels, nudging me to “his favorite” brand/bottle/varietal.

I consider shopping to be a leisure time activity, taking all the time in the world to consider my options.

As a wine writer I really like to look at the labels, move from the French to the Italian section, meander through the Spanish section, and even look at what is available from New York, California, Missouri, Arizona, Texas as well as Israel, Portugal, Australia, China, and Kosovo.

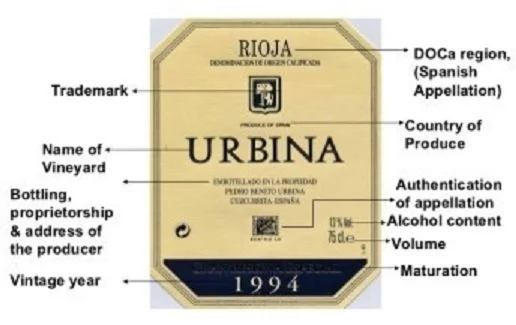

One way to address the wine shop hustle is to quickly read the label on the wine bottle, walking out with the wine desired and not the bottle the staffer wants to sell me.

Spanish Wine Label 101

The Spanish wine label is a map leading to what is waiting inside the bottle.

1. The Name of the Wine

2. Vintage. Year or Place/Location wine, especially wine of high quality (i.e., DO Denominacion de Origen), was produced.

• Not every year is a good year for wine. Some years are better than others.

• Each DO has its own unique character, and taste. The only way to determine a personal preference is to taste it (trial and error).

3. Quality of the Wine. Spain requires a minimum of aging in the bottle and in oak barrels for it to be considered Crianza, Reserva, or Gran Reserva:

• Crianza. At least one year in oak barrels

• Reserva. 3-year-old wine with at least 1-year spent in oak barrels

• Gran Reserva. Wines aged for a minimum of 5-years: 2-years in oak barrels, and 3-years in bottles.

Colors of Wine

Wines are frequently selected to enhance a dining experience; however, many wines are able to hold their own and are fabulous to sip without food:

o Blanco – White

o Rosado – Rose

o Tinto – Red (Spanish word: ROJO; however, red wines are known as Vino Tinto)

Types of Wine

o Cava – sparkling wine made in the traditional method (think Champagne)

o Vino Espumoso – Sparking Wine made in different parts of Spain and are therefore not permitted to use the word CAVA on the labels as they do not confirm to rules stipulated by the Cava regulatory body

o Vino Dulce/Vina para Postres – Sweet or Dessert wine

Official Categories

o DOCa – Denominacion de Origen Calificada. Only wine making regions proven to offer consistent top-quality wines (i.e., Rioja and Priorat)

o DO -Denominacion de Origen. Wine made under the supervision of a DO is protected by law. Historically DO wines are considered the best quality; however, recently wines that are not DO have equaled or exceeded DO wines

o Vina de la Tierra (VdLT). Wines from a specific geographical area. In other time periods, these wines were considered “second best.” This is no longer true.

o Parcelario. “Unofficially” – term referencing a wine made from grapes grown in one specific plot.

o Vino d’Autor. Reflects the winemaker’s personal style, and carries his/her name. These may (or may not) conform to the DO or VdLT regulations.

o Vina de La Mesa. Table wine located at the bottom of the Spanish wine quality ladder. However, this is not always true. There are some wines made in the DO or DOCa areas that do not meet the rules designed by the Conselo Regulador (Regulating Council) of the region, and the wines have to be labeled Vina de La Mesa. In fact, these wines may be more expensive than the approved DO wine from the same area.

Other Terms

o Roble – Oak! This word is located on the back of labels, provides information on the amount of time the wine has spent in oak barrels. On the front of the label, refers to oak – telling the style of the wine. This usually suggests that the wine has spent less than six months in oak (3-4 months). If the wine has been oaked longer, it will likely be termed Crianza or Reserva.

o Barrico – Barrel. Frequently followed by American (American oak) or France (French Oak), indicating the provenance of the wood.

Allure of Spanish Wines

Pablo Picasso was inspired by the towns, vineyards, and people of the Spanish wine region (Terra Alta) during his 20s when in lived in the mountains. The world is slowly acknowledging the wisdom of Picasso with Spain consistently rated among the top three wine producers in the world (France and Italy are the other two).

Evidence suggests that grape vines have been cultivated in Spain since 4000 – 3000 BC. The Phoenicians started making wine in 1100 BC in the modern-day locale of Cadiz and traded it as a commodity, using heavy, fragile clay containers (amphorae) for transporting.

Phoenician Maritime Amphora

The Romans followed the Phoenicians in controlling Spain, planting vines, introducing their winemaking skills to local residents (i.e., Celts, and Iberians). The practices were embraced including fermentation in stone troughs, and the use of more resilient amphorae. During this period, Spain exported wine to Rome, France and England.

The next group to rule Spain were the Islamic Moors of Northern Africa (8th century – 15th century). The Moors did not drink alcohol; fortunately, they did not impose their beliefs on their Spanish subjects although innovation in winemaking was stalled during this period. In the middle of the 13th century, wine from Spain was shipped from Bilbao to England; however, the quality of the wine was inconsistent but the very good wines competed successfully with French and German offerings.

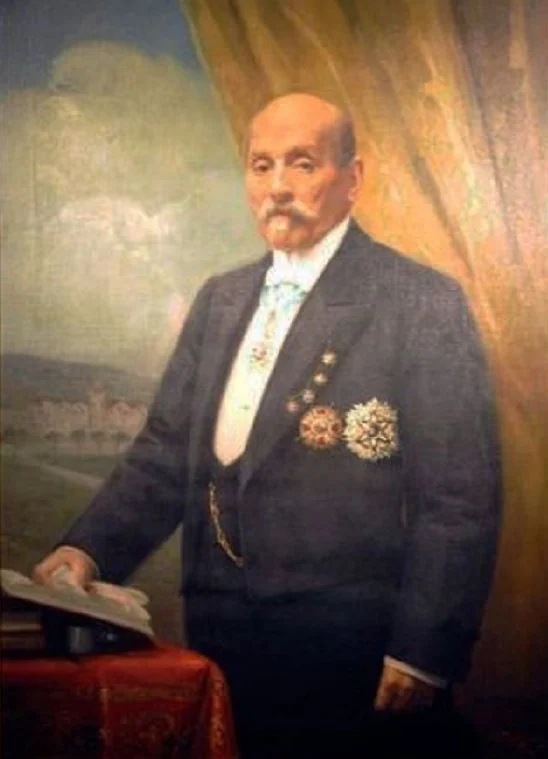

When the Moors were defeated in the 15th century, Spain was united. Columbus “discovered” the West Indies giving Spain a new world market. In the middle of the 19th century the foundations of modern Spanish winemaking were established by winemakers from Bordeaux, Luciano de Murrieta Garcia-Lemon (the Marques de Murrieta), and Camilo Hurtado de Amezaga (the Marques do Riscal). These men brought Bordeaux technology to Rioja, and Riscal planted a vineyard in Elciego, starting a bodega in 1860. In 1872, Murrieta started his own bodega, the Ygay estate, and the rest is history.

Following in these footsteps, Eloy Lecanda started to professionally make wine in 1864 on the estate currently known as Vega Sicilia. With a background in Bordeaux, he brought French oak casks to the area, along with new winemaking skills, and grape varieties, finding that the vines successfully grew next to the native Tempranillo.

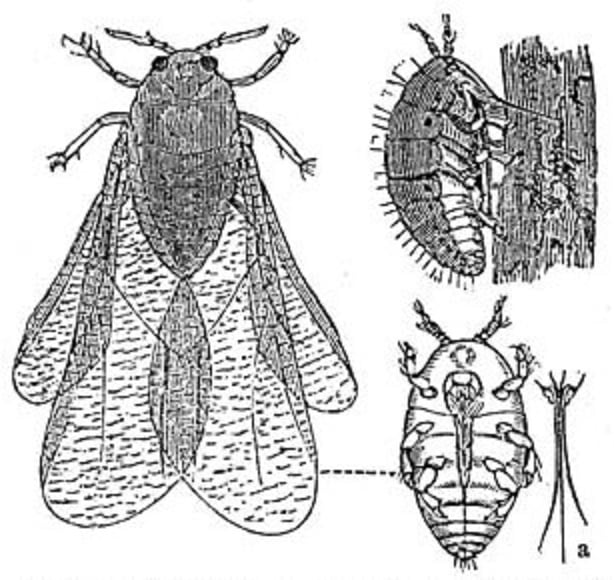

Phylloxera spread to Spain during the 19th century, invading Rioja in 1901. Although a solution had been developed, vineyards throughout the country had to be replanted.

Many indigenous grape varieties were facing extinction.

Spain entered a period of political unrest which ended with right-wing General Francisco Franco was victorious, ruling Spain as a military dictator from 1939 until his death in 1975. The Franco regime suppressed economic freedoms including wine which he believed should be used only for church sacraments, removing vineyards in Viura and other regions.

When Franco died, Spanish winemaking gained traction and there was a new interest in high-quality wines by the urban middle class. Spain joined the European Union in 1986, and new investments were made in Spanish wine regions with better production methods and extensive modernization.

Spanish Wine Future

Currently, the Spanish wine segment equals to US $9,873m (2022), and the market is expected to grow annually by 6.24 percent. It is projected that by 2025, 79 percent of spending, and 52 percent of volume consumption in the wine segments will be attributable to out-of-home consumption (i.e., bars and restaurants). Spain is the world’s number 1 producer of organic wines with more than 80,000 hectares registered and documented for organic production. The leading producer, Torres, had one-third of its vineyard producing organics.

Spain continues to face the issues of climate change as warmer climate advances the harvest season, increasing the need for more heat-tolerant grape varieties. Higher temperatures have brought the grape harvest forward by 10-15 days over the past decade, and harvests now takes place in August, when the heat is the most intense. To offset this challenge producers are moving their vineyards to higher elevations.

Do You Fit?

Research finds that 60 percent of the Spanish population considers themselves wine consumers with 80 percent enjoying wines are a regular basis, and 20 percent drinking occasionally. The vast majority of these drinkers prefer red wine (72.9 percent), while others prefer white wine (12.0 percent), rose (6.4 percent), sparkling wine (6 percent), and sherry/dessert wines (1.8 percent). Most people are drinking at home rather than at bars and restaurants and this may be because of the price differential.

Now is the perfect time to explore the beautiful and delicious wines of Spain.

For additional information, click here.

This is a series focusing on the Wines of Spain:

Read Part 1 Here: Spain Ups Its Wine Game: Much More Than Sangria

Read Part 2 Here: Wines of Spain: Taste the Difference Now

Read Part 3 Here: Sparkling Wines from Spain Challenge “The Other Guys”

© Dr. Elinor Garely. This copyright article, including photos, may not be reproduced without written permission from the author.